Tools

Developmental editing requires good decision making.

What do you base those decisions on?

Let’s make some tools to help inform those decisions.

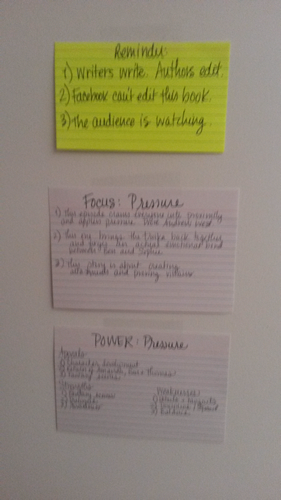

TOOL 1: Reminder

The first weapon is a simple reminder. On the first index card, write the following:

- Writers write.

- Facebook can’t edit this book for me.

- The audience is watching.

TOOL 2: Focus

Take out another index card and prepare to write small so that everything fits on one side.

- In 20 words or less, describe how this story idea came to be:

- In 20 words or less, describe what excited you most about this idea:

- In 20 words or less, explain what this story is really about:

TOOL 3: Power

Here’s the last index card. Conserve space again so everything fits on one side.

- List three things about this book that will appeal to its target audience:

- List your top three weaknesses as a writer:

- List your top three strengths as a writer:

Post those tools somewhere highly visible in your workspace.

TOOL 4: Style Guide

Create a style guide: list words and information to help protect against inconsistency, continuity errors a/o irregularities.

Make a list of:

- Locations/location names

- Names

- Deliberate misspellings

- Deliberate non-standard capitalization

- Words that don’t or won’t pass Spellcheck

- Words containing special characters like umlauts, grave and acute accents, or &c.

Can also list particularities similar to these examples to protect continuity:

- Ages

- Dates

- Professions

- Physical descriptions

TOOL 5: Notebook

A notebook for revision notes. (I don’t recommend digital documents for these: writing drags other parts of your noggin into the process, and that can add a lot to this process.)

It’s important to resist the urge to bust into developmental revisions the second inspiration strikes. TAKE NOTES INSTEAD. Almost 100% of the time, those off-the-cuff revisions will have to be revised again—often more than once. Don’t waste the time; take notes first instead, complete all these tools, then revisit the revision notes when you can see the forest from the trees. Or the trees from the forest, as the case may be.

TOOL 6:Scene Index

Tool: In a spreadsheet, create a scene index, listing every scene in the order they appear.

Add columns with headers you find important, such as “the point of this scene” or “time” or “location”; index information that helps organize or streamline storylines and your thoughts. If you’ve any pet writing theories (9-Act, Mythical Structure or &c.) check them against this index.

Warning: Creating this index can have brain-charging results.

Remember—don’t get sidetracked. Take lots of clear notes, but make no actual revisions until all tools are complete.

Shoot each scene with Chekhov’s Gun: What’s the purpose of this scene? Why is it in the story? What purpose does it serve?

Take notes about what could be cut, combined or otherwise streamlined.

TOOL 7: Questions Index

Semantics: “Conflicts” could replace “questions”. So could “Dilemmas”. Different words, same concept.

Tool: In a fresh spreadsheet, create a list of every question posed in the story, from the biggest, global question (Who killed Bob? Or How will Dylan and Miranda fall in love?) to the smallest of secondary questions (How did Bob die? or Why did the villain kill Bob? Or Why is Miranda afraid to fall in love with Dylan?)

Intro And Outro

In the Questions spreadsheet, add an Intro column and an Outro column.

Copy-and-paste the sentence or paragraph where each question enters and exits the story.

Collide and Resolve

In the question spreadsheet, explain how each question collides with or fuels others.

Then explain how each question is resolved.

Juxtapose

What if each question was the story’s central question? (Instead of who killed Bob, maybe we know who killed Bob, and the central question becomes why Bob was killed.) How would the story be different? How would it be better?

What’s the point?

Shoot each question with Chekhov’s gun: what purpose does it serve? Is it fully realized? Cut a/o combine to get rid of frayed tangents.

TOOL 8: Characters

Tool: In a fresh spreadsheet, create a list of every named character in the story.

Neurology is not your friend

Check their names: do first names or surnames have the same number of letters, or do they all start with the same letter? Make each name visually distinct.

Intro And Outro

On the spreadsheet, copy-and-paste the sentence where each character enters and leaves the story.

Is this the best (most dramatic, most characteristic, most telling, most fulfilling) way they can enter a/o leave the story?

Collide and Resolve

On the spreadsheet, explain how each character complicates things for the other characters.

Then explain how each character’s individual storyline is resolved.

Juxtapose

What if each secondary character was the hero of the story? How would the story be different? How would it be better?

What’s The Point?

Shoot each character with Chekhov’s gun: What purpose do they serve? Are they fully realized?

Consolidate or combine to get rid of dead weight.

Clarity

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked … A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over, beginning with a working simple system. — Grady Booch

Think of each character and question/conflict/dilemma as a simple system. Each must have its own complete throughline. Each must stand alone, complete and fully realized. Make each simple system a working system—if one system is broken or incomplete, the complex system (story) is broken.

Revisit, Regroup & Revise

Now that all of these tools are assembled, go back and revisit the notes taken along the way.

Go back further to revisit the first three tools assembled:

- Which revisions will best please a/o satisfy the reader?

- Which revisions will best highlight your strengths and compensate for weaknesses?

- Which revisions will help preserve the dynamic spark that fuels the story?

Sorted yet?

Good. Get busy.